Moon Suits In My Yard: Settler Colonialism, Industrial Contamination, and an Indigenous Community’s Fight for Environmental Justice

Elizabeth Hoover, Brown University

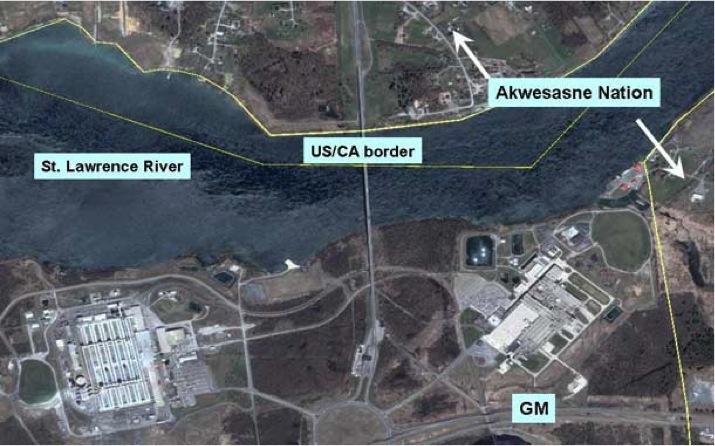

“This is God’s country here,” an Akwesasne Mohawk woman explained to me as we sat at her kitchen table over cups of coffee. She stared past me out her kitchen window that overlooks the St. Lawrence River, and the General Motors plant. She had just been describing how she stood in her front yard and watched men in “moon suits” work to clean up the industrial site a few years prior. “They’d come in here in their space suits and take your water, a sample of it. If that’s not alarming, then I don’t know what is.” She described how “we used to play in that dump. We used to go play in it. We would just scavenge in the junk and go sort through it, pick aluminum and stuff like that, play with paint.” When the Tribe issued fish advisories, recommending that women of childbearing years limit or avoid consuming local fish, her family quickly changed their diet. But she’s not sure these changes came in time to protect their health; she had always wanted a big family, but several miscarriages made that impossible. But when I asked her if she ever considered moving, she said no, echoing the answer of one of her neighbors further down river who had exclaimed, “Are you kidding me, I live in heaven!” As a resident of the Raquette Point region of the St. Regis Mohawk reservation, she has the dubious honor of both beautiful waterfront property, and a front row seat to observe a Superfund cleanup.

These conversations are emblematic of the complicated feelings that many Akwesasnero:non, "people of Akwesasne," expressed about their homeland, a place that has sustained indigenous people for eons but which has been impinged on by environmental contamination as well as state and federal governments. As people reputed to be fighters and activists, Mohawks have fought to preserve who they are, confronting state and federal governments and the scientific industrial complex to maintain their homeland. Despite a number of political and social challenges, when it was discovered in the early 1980’s that the General Motors industrial plant directly adjacent to the Raquette Point portion of Akwesasne had been leaching PCBs into the St. Lawrence River, the community came together and sprang into action. A midwife, Mohawk scientists, and community members, concerned about the potential health impacts of this contamination, worked to revolutionize how environmental health research is done in Indigenous communities, and pushed to influence how the cleanup would be conducted. Despite the ways in which environmental contamination has contributed to the goals of settler colonialism—displacing Indigenous people from the land both physically and culturally, communities like Akwesasne are fighting back by developing their own environmental governance structures and forging the necessary partnerships to carry out important environmental health research.